By Kristen Hannum –

Kent Argow’s father was scanning the horizon with a pair of binoculars during one of the father and son’s many visits to fire towers.

“Dad saw smoke,” Argow says.

That fire hadn’t been reported yet, and the father and son had front seats as they witnessed what happened next.

Argow, now the director of the Colorado and Utah Forest Fire Lookout Association, still remembers the thrill of that day. The fire watcher called in the location and before long a spotter plane flew by the tower, tipping its wing to salute the spotters. Next came the huge plane filled with smoke jumpers. “We watched them throw their toolbox out,” Argow says. The parachute snapped open for the box, and then came the jumpers themselves. Argow and his father also watched helicopters dumping water on the flames.

“By that night they’d snuffed out the fire,” he says. “It was an unbelievable experience, and we just happened to be there.”

Although fire towers have largely been phased out in favor of spotters in planes (and perhaps drones in the future), a few fire towers are on the first line of defense against massive fires. What’s more, a handful of fire towers in Colorado offer great — and potentially thrilling — summer adventures.

Sondra Kellogg, Argow’s predecessor at the Fire Lookout Association, is a former fire spotter who lived in the Thorodin Tower during the summer of 1960 and 1962. She describes the towers as being a perfect summer destination, combining history, stunning views, great hikes and a lesson on fire prevention and fire fighting. Not only that, but just by visiting the towers, citizen hikers can also help preserve the historic structures from vandals.

There are even two Colorado fire towers — Jersey Jim Lookout in the San Juan National Forest in southwestern Colorado and Squaw Mountain Fire Lookout Cabin at the summit of Squaw Mountain in the Clear Creek Ranger District along the Front Range — that you can rent and stay overnight in.

That can present a different kind of excitement: lightning.

Kellogg was in the Thorodin tower when lightning hit the steel guardrail that circled the catwalk outside the cabin. She could smell the ozone and feel the electricity in the air, the hair standing up on her arms. Kellogg and her then-husband were forewarned on what to do: unplug the telephone and sit on the bed. “Everything was grounded,” she says.

Today’s fire tower guests are reassured that they’ll be safe too, even in a lightning storm, as long as they follow the rules. Just don’t lean against that metal stove…

Fire towers include a couple that Argow describes as being appropriate destinations for “anyone who could handle one of Colorado’s fourteeners.” Other towers are towers in name only; one in Mesa Verde is wheelchair accessible.

The golden age of fire towers started in the early 20th century, when early forest rangers — including the country’s first forest ranger, William Kreutzer, who lived here in Colorado — realized that spotters in a tower could sound the alarm when they saw smoke.

It took almost inconceivable grit to build some of the lookouts, with materials lugged in on mule, horse and human backs.

Seeing a fire wasn’t much good unless a spotter could get word out, and the earliest fire spotters used carrier pigeons and heliographs, mirrors that could reflect sunlight in a code. Telephone lines were a vast improvement.

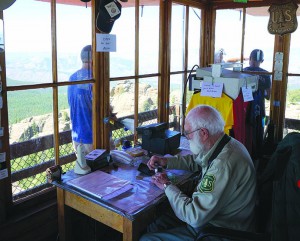

Both 100 years ago and today, it was crucial that fire spotters be able to transmit precise information on a fire’s location. Spotters at Colorado lookout towers, like the one at Devil’s Head near Sedalia, still use the Osborne Fire Finder, invented in 1915, a kind of manual global positioning system for pinpointing the location of fires.

In their heyday, there were 8,000 lookouts across the country. They were in every state except Kansas. Idaho alone had more than 900.

Air patrols were the beginning of the end for the towers, which by the 1970s seemed romantic but old-fashioned.

Only about 2,000 towers remain, with less than 30 in Colorado. “Why Colorado got rid of so many I don’t know,” Kellogg says.

She does know what happened to her tower. The Thorodin Tower blew over in the 1930s. It was rebuilt but in the 1980s 100-mile-per-hour winds blew the cab off. No one was hurt, since it hadn’t been staffed since the late 1960s.

The most recent tower to disappear, the Chimney Rock Lookout, was dismantled in 2010.

That being the case, this weekend might be the best time to grab your camera, pull on your hiking boots and head out to visit one of these endangered and magnificent structures.

You might even spot a fire. “That can happen at any point for anyone,” Argow says, who speaks from experience.

Colorado lookouts you may want to visit:

Devil’s Head Lookout (9,708 feet) is near Sedalia in Pike National Forest. This is a classic, perched atop a dramatic stone cliff, accessed by 143 steep steps and staffed for the last 32 summers by the amazing 83-year-old Bill Ellis. America’s first forest ranger, William Kreutzer, was also from the area, and might have used the summit where the lookout now stands to scan for fires.

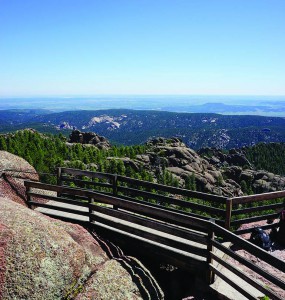

Devil’s Head, at the highest point of the Rampart Range, was one of four primary lookouts along the Front Range. The one-and-a-half mile hike there begins in light-dappled stands of aspen and then climbs until the trail reaches a steep red stairway ingeniously ascending the towering granite outcropping. “If you want a snapshot of what it’s like to man a fire tower, that is the experience there,” Argow says.

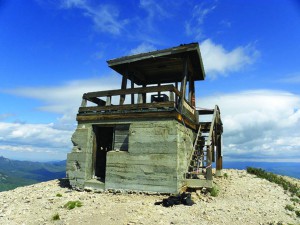

Hahn’s Peak Lookout (10,759 feet) in the Routt National Forest near Steamboat Springs also offers 360-degree views of the surrounding mountains and valleys. The lookout, built between 1908 and 1912, was used less and less in the 1950s, until it finally became little more than an iconic landmark, visited by hikers and vandals alike.

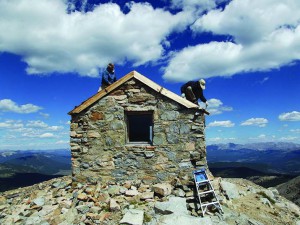

This summer marks the best time to hike to it in the last 50 years or more. That’s because it was awarded funding for a complete restoration, work that has taken place since the beginning of summer. It’s a challenging 4-mile hike (trail 1158, Hahn’s Peak trail) with loose scree close to the peak’s bare top.

Deadman Lookout (10,710 feet) in the Roosevelt National Forest, about 5 miles due west of Red Feather Lakes, is a good 10 miles on gravel roads if you’re driving rather than flying with the crows. Deadman is a great example of a modern lookout tower. Built in 1961, the 55-foot tall steel tower is well-staffed by knowledgeable volunteers who can answer every question — and show off the view from the cab atop the tower.

Shadow Mountain Lookout (9,923 feet) is in the western portion of Rocky Mountain National Park. Its stone base supports a one-room cab surrounded by a catwalk. The Civilian Conservation Corps built it in 1932, and it was known as one of the finest “parkitecture” buildings in the country. Now it’s the only remaining fire lookout in the Rocky Mountain National Park, staffed in 2012 for the first time since 1969.

The trail leading to it is 4.8 miles and is considered an intermediate trail, with an elevation gain of 1,533 feet. The lookout boasts a view of mountain lakes and the Fraser River Valley that is all the sweeter for the effort it takes to get there.

Jersey Jim Lookout (9,830 feet) in the San Juan National Forest has a loyal following of locals who constitute a good percentage of the people who rent it during the summer months. Similar to Deadman Lookout in age, style and height, it’s also similar in that it’s accessible to two-wheel drive vehicles along gravel forest roads. Folks staying there have a choice of porting their supplies — including water — up its steps or via a pulley lift. The Jersey Jim Foundation rents the lookout for just $40 a night and typically books the entire summer within days of opening reservations in March.

Park Point Lookout (8,572 feet) in Mesa Verde National Park is just 0.2 miles on a paved, wheelchair-accessible walkway from your car. It sits at the highest point of the park, an octagonal groundhouse made of local sandstone. Signs tell you what you’re seeing in its 360-degree view spread out below. It’s staffed during the fire season.

Fairview Peak Lookout (13,214 feet) in the Gunnison National Forest is at the other end of the spectrum from Park Point Lookout, both in terms of ease of access and upkeep status. Beginning at Gold Creek Campground at 10,200 feet, hikers must climb 3,000 feet to Fairview Peak’s summit. A short season and afternoon lightning storms mean volunteers have little time to work on repairs.

Kreutzer commissioned this lookout in 1910, perhaps not one of his best decisions. Although fire spotters had stunning views of the Pitkin and Tincup districts, lightning forced its abandonment within a few years. Need it be said? Visitors should plan to be off the peak by early afternoon.

Chimney Rock Lookout (7,903 feet) in the Chimney Rock Archaeological Area of the San Juan National Forest is easy to get to. This is a “ghost” lookout, built in 1936 by the Civilian Conservation Corps and dismantled in 2010 because it was built on the site of a 1,000-year-old fire pit using blocks from nearby ruins. Access is by gravel road and then a half-mile walk.

The spectacular views from the site show why people in any era would use it for a lookout. Falcons nest here; it’s closed for their sake in spring.

Squaw Mountain Lookout (11,486 feet) is the other Colorado lookout available for rent year-round. There’s no water available, nor is there a garbage service, meaning that visitors should plan to pack their supplies in and pack their trash back out. A high-clearance vehicle is advisable for reaching the parking lot, and winter visitors should be prepared to snowshoe or ski to the site. Contact the Clear Creek Ranger District in Idaho Springs for more information.

Squaw Mountain Lookout (11,486 feet) is the other Colorado lookout available for rent year-round. There’s no water available, nor is there a garbage service, meaning that visitors should plan to pack their supplies in and pack their trash back out. A high-clearance vehicle is advisable for reaching the parking lot, and winter visitors should be prepared to snowshoe or ski to the site. Contact the Clear Creek Ranger District in Idaho Springs for more information.

Kristen Hannum is a Colorado native who splits her time between rainy Colorado and the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest. She’s made her living as a writer and editor her entire adult life, writing articles for a number of magazines and newspapers. She says Colorado Country Life is the best.