Colorado Couple Helps Preserve Bovine Heritage –

By Gayle Gresham –

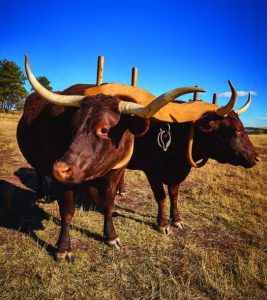

These aren’t the usual Angus or Hereford cattle most often found on Colorado ranches. The pair of sturdy, dark red animals with beautiful, curved horns don’t look like any of the often seen Colorado ranch cattle. They are not Texas longhorns. There is something different about them — something more historic, something that makes them seem like they just stepped off the pages of a history book. And that’s not too far from the truth.

They are American Milking Devons. Rollie and Paula Johnson spent the past 10 years raising, preserving and promoting this critically endangered breed on their Three Eagles Ranch, tucked among the ponderosa pines along the Palmer Divide southeast of Larkspur.

The Milking Devon has the distinction of being the first breed of cattle imported from England to the American colonies in 1623, when King James shipped three heifers and a bull from north Devonshire. The seed stock not only supplied milk and beef for the Pilgrims, who went two years without any cattle, but also provided oxen to be used as draft animals. According to tradition, the first plow to turn over a furrow in what is now Massachusetts was pulled by a Devon ox.

During the westward expansion in the 1800s, the Milking Devon proved to be a popular breed of oxen as Milking Devons pulled covered wagons over the Oregon and Santa Fe trails, as well as over other trails leading West. However, once westward expansion slowed and the railroads took over, the numbers of Milking Devon declined in the United States. Breeds such as Holsteins and Jerseys could produce more milk, other breeds of cattle produced more beef and oxen became obsolete with the invention of tractors and trucks.

“When we started raising American Milking Devons 10 years ago, there were about 600 in the United States. And none in England,” Rollie says. He explains that the Devons were crossed with other breeds in England until no more full-blooded Milking Devons were left there.

Raising American Milking Devons

Today there are approximately 1,600 of the breed in the United States, primarily in New England. The Johnsons did their part to increase the numbers in their 10 years of raising the unique cattle.

It all started when they were raising registered Angus cattle. “Paula was naming all the calves, and it felt like we were eating our own pets when we butchered one,” he says. “We found something about American Milking Devons in a magazine called Hobby Farms and learned the boys were able to grow up and become useful as draft animals. So, we went to a conference and decided it was a breed we would like to get in to.”

The Johnsons bought their first cow from a farm in Missouri and their bull, nicknamed Jesse James, came from George Washington’s Birthplace Farm near Williamsburg, Virginia.

“We raised 100 calves, about 50 percent of them were heifers that became registered mothers, and we trained about 50 steers as oxen,” Rollie recalls. “Of those, we had one that was goofy and wild (not suited for drafting) that we butchered. In all, we created about 25 pairs of oxen and raised a few bulls.”

An ox is a steer (a castrated bull calf) that is 4 years old or older and trained to be a draft animal. Rollie and hired hand Dulces Granados, who has worked for the Johnsons for the past 11 years, begin working with the calves or imprinting right after birth so they get used to being handled and around humans in a nonthreatening way. The calves are also always worked as a pair so they get used to working together.

At 6 weeks old, training begins in a 4-inch yoke with bows made of PVC pipe. As the steer grows, it progresses to a 5-inch yoke at 8-10 weeks of age, and is in a 6-inch yoke by the end of its first year. An ox is considered mature at the age of 7 and can weigh 2,000 pounds or more. Seven is also the age when the hump over the neck begins to develop, which holds the yoke in place and allows oxen to oxen, are in a 10-inch yoke and might grow into an 11-inch yoke.

The yokes that lay over the top of the necks of the oxen are hand made by the Johnsons just as they would have been made by the pioneers. Cottonwood or chestnut is used, and the yoke is taken from the outer part of the trunk. The bows are 2 inches of hickory that are bent by using stones in a steam box that will hold the shape. They are then dried. Metal pins hold the bows in place and are adjustable to size. A large yoke can weigh almost 100 pounds.

Each calf is named after a U.S. president or first lady starting with the first calves, whose names began with the letter “A.” Clark and Coolidge were the first oxen team trained by Rollie. “Clark and Coolidge are now at Bent’s Old Fort near La Junta,” Rollie says. “They used American Milking Devons in the 1830s to take loads of furs from Bent’s Fort to Kansas City and bring beads and ammunition back.”

Three Eagles Ranch sold teams of oxen to other historical sites in Colorado and across the country, including Fitz and Ford who reside at the Littleton Museum and Calvin and Chester at the Plains Conservation Center in Aurora. Last year, the Johnsons sold a pair to the Orange County Fairgrounds in Costa Mesa, California. It is a Centennial farm where more than 80,000 children, most of whom never saw a cow before, visit each year and have the opportunity to hear the story of oxen settling the West.

The role of oxen in settling the West

The value of the American Milking Devon as oxen lays in their intelligence, calm demeanor, the amount of strength compared to their size, and the ability to listen well. The breed also does well on the native grasses of the West and can walk up to 6 miles per hour. All of these characteristics made it desirable for pulling the wagons across the plains and Rocky Mountains.

Rollie explains that there are two reasons oxen were used extensively in settling the West. The first was cost. “They were cheaper than a pair of horses or mules, basically by a tenth — $50 for a pair of oxen versus $500 for a pair of horses.

“The real reason,” he says, “was because oxen could walk and eat at the same time, whereas a horse can’t. You’d have to take a wagon-load of grain for a horse in order for the horse to haul all of the furniture. And the trails, we think of a trail as a road, but the first group would start out by the river and the oxen would eat the grass along the trail. The second group would start further over and eat that grass. By the end of the season, the trail could be 20 miles farther away from the river.”

The pioneers didn’t ride in the wagon as you might expect. They loaded their wagon with their belongings and walked alongside of it. “It meant a barrel of wheat could be carried instead of two people riding in the wagon,” Rollie says. The oxen were driven by walking along beside them, using a goad (a stick) or a small whip snapped in front of them to get their attention. The commands, “gee” for right and “haw” for left, were spoken.

Oxen also offered a food source if it became necessary. If one died on the trail, it would be butchered. Or they could supply the winter’s meat after arriving at a destination. More often, however, oxen were used on the homesteads to plow fields and in logging. In other words, oxen not only helped settle the West, but also helped to build it, too.

Living history

The Three Eagles Ranch oxen are becoming celebrities with credits that include a Netflix series and a documentary. Last November, the Johnsons took two teams of oxen (7-year-olds Davey and Dandy and 4 year olds Grant and Garfield) to the Bonanza Creek Movie Ranch near Santa Fe, New Mexico, to be filmed in the Netflix series “Godless.” The show is about fictional 1880s outlaws and will premiere this year. The Johnsons were there for filming two and a half days, along with Dulces and another friend who also helped with the oxen. In one scene, the oxen were tied to trees for about eight hours at a campsite where guest star Jeff Daniels had a shoot-out. Scenes on another day included the two teams pulling covered wagons for two families, with children following behind the wagons.

In August of 2015, Rollie, Paula and Dulces took the two pairs of oxen to Martin’s Cove, Wyoming, and Chimney Rock, Nebraska, to appear in a documentary on the Oregon Trail filmed by the Museum of Westward Expansion at the St. Louis Gateway Arch. The Johnsons and Dulces plan to attend the grand reopening of the museum this summer where the documentary will premiere.

Dressed in period clothing, Rollie and Dulces walked 15 miles for take after take for just one day of filming. It gave them a feel for how tired the pioneers were who walked 15 miles a day for 1,900 miles on the Oregon Trail. Paula also dressed as an extra for the documentary.

Paula mentions the posts at Martin’s Cove with the names of the trails on each side — Oregon Trail, Mormon Trail, California Trail, Pony Express — where trails crossed.

“It gave me goosebumps to stop and look at the names on the posts and to realize there we were with our oxen where so many went before us,” she says. “It was eye-opening.”

The past year was a time of change for the Johnsons and their love affair with the American Milking Devon. Their bull, Jesse James, developed Brisket disease (pulmonary hypertension caused by high altitude) and had to be moved to a lower elevation. They decided to sell their cows, too, and the herd moved to a ranch in South Dakota.

The Johnsons plan to maintain a smaller herd of working oxen including the teams of Davey and

Dandy and Grant and Garfield. They will continue to take the oxen to schools, county fairs and historical exhibits in Colorado and the West. So, while they no longer raise cattle, Rollie and Paula remain tightly yoked to the living history of the American Milking Devon.

Gayle Gresham is a writer living in Elbert. Her great-great-grandparents came to Colorado in 1861 in a covered wagon pulled by oxen.