By Kristen Hannum –

May The Pikes Peak Guy knew odds were that he’d eventually meet a bear as he wandered the roads, main trails, back routes and dead-end deer paths around Pikes Peak. The rendezvous appropriately took place on Friday the 13th in August 2010.

He was 10 weeks into a year of shooting photos of Pikes Peak and publishing his best image every day on The Pikes Peak Guy’s Facebook page, a project that eventually became a 4.6-pound book, 365 Days of Pikes Peak: The Journey, and would change his life.

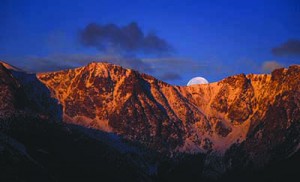

But on that Friday, The Pikes Peak Guy was out by himself with just his camera for backup. The sun had set; the photo for the day would be a time-lapsed image of the night sky over “America’s mountain,” the stars looking like dozens of delicate incisions in the dark violet canopy.

But on that Friday, The Pikes Peak Guy was out by himself with just his camera for backup. The sun had set; the photo for the day would be a time-lapsed image of the night sky over “America’s mountain,” the stars looking like dozens of delicate incisions in the dark violet canopy.

“The smell of something foul hit me,” The Pikes Peak Guy wrote in the day’s Facebook entry. The hairs on the back of his neck stood on end as he shone his light over his shoulder and saw a bear staring back at him.

A bracing jolt of panic came with thoughts of which body parts to protect first, but then he remembered to shout, not run. The bear turned and walked away.

The Pikes Peak Guy then began carrying a gun as well as his camera on those daily shoots.

As summer turned to autumn, and then blew into winter, more people in Woodland Park discovered The Pikes Peak Guy was their neighbor Shaun Daggett, who was by day the mild-mannered executive director of corporate development for an international translation firm for businesses.

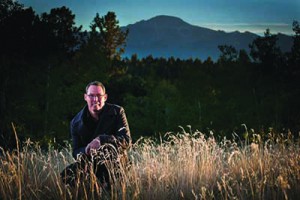

Pikes Peak Guy Shaun DaggettDaggett’s path to shooting 365 Days of Pikes Peak: The Journey was as winding as that trail where he’d met the bear. In fact, his trajectory goes against much of what we all know makes for success. “It worked because I didn’t plan it,” Daggett says.

“I think that’s right,” says Daggett’s longtime friend Damon Williams. “Had he put a lot of planning into it, he would have talked himself out of it. He says, ‘I love the book, but I would not do that again.’”

On the other hand, Daggett likes the saying that “luck is where preparation and opportunity meet.” And while he might not have thought through what it would take to post a first-rate photo of Pikes Peak online every day, he did have the photographic chops to make it work, and he had the business know-how to sell his art.

Daggett left home at age 18 to attend photography school. An early marriage and four children pushed him onto a corporate track instead. Since the 1990s he held a number of challenging positions that came with a solid salary and the perks of international travel. Then, in 2000, he, his wife and four children moved to Colorado after he received a job offer. They fell in love with Woodland Park, a town 19 miles northwest of Colorado Springs. Woodland Park, not coincidentally, is known for its spectacular views of Pikes Peak.

But Daggett wasn’t happy. He hesitates to admit that because he knows how fortunate he was. But he wasn’t doing what he dreamt about while growing up.

By spring 2010, Daggett was single again and he had his son, Jared, a high school junior, living with him. It was the right time to take a shot at his first love: photography. He would go at it not just with a camera but with all the canny smarts he learned in his corporate career. It would be, as he says, “landscape photography on steroids,” a published photo per day from June 1, 2010, to May 31, 2011.

“He’s super ambitious; once he gets his mind set, nothing will stop him,” says Jared.

“He’s super ambitious; once he gets his mind set, nothing will stop him,” says Jared.

JuneOther than the bear, August 13 wasn’t unusual for Daggett’s year. The day began with grabbing a cup of coffee at 4:30 a.m., driving out to a remote site, setting up his tripod and waiting for the sun to rise. It wasn’t a remarkable sunrise, and so, after putting in a morning at his day job, Daggett drove out again at lunchtime to check out the midday light. Those photos didn’t satisfy him either. And so, after work he set out again that evening.

“I went out there happy, dumb and lucky,” Daggett confesses. “Nobody knew where I was. I would have been in real trouble if I’d gotten stranded.”

He typically got back home after dark and headed to his computer to review and edit his shots from the day, usually a couple hundred but sometimes as many as 500 digital images in a single day. It took hours to sort through them all.

After choosing the day’s best shot, Daggett wrote about how he took the shot, including the technical specifications, then posted it to Facebook by midnight. That was a hard deadline. “I was publishing the picture of the day — not the day before — every day,” he says. “There were no breaks, no vacations, no holidays, no Christmas. I was a single parent, engaged at the time. I held a full-time job, had all the responsibilities of life. It didn’t matter if the dog got sick or the truck broke down, I had to make it work. I couldn’t do a halfhearted project on America’s mountain.”

April It was, by all reckoning, an insane project, one that put 33,000 miles on Daggett’s old truck.

Yes, the dog, Mac, did get sick a couple times and the truck had problems more than once. Son Jared put it into a ditch several times. “I’d just gotten my license,” Jared explains.

Daggett says Jared, a hiker and mountain biker, was his greatest help along the way. Jared scouted for locations, hauled equipment and framed shots for his dad. “He took care of a lot of things at home and helped me, especially when I was sick,” Daggett says. “He was like my Sherpa. I’d say, ‘Hey scurry up those rocks. Is there an interesting view up there?’”

If there was, Daggett would scramble up with the equipment to shoot some photos.

“I don’t think I could do it again,” Daggett says. “By the time it was all said and done, I was drained physically and emotionally. I slept for a couple weeks afterwards.”

And then?

“Then we had to start doing all the work for the book,” says Jared.

That had already actually begun with the decision to self-publish an expensive prospect. Daggett launched a Kickstarter campaign, an online appeal to donors interested in funding creative projects, before he finished his year of shooting. He raised $17,864 from 150 backers, the fundraising ending on May 31, 2011, his last day of shooting. That campaign was the third highest fundraiser on Kickstarter at the time in the photography category.

Daggett produced a coffee-table book priced at more than $100. He had an enthusiastic following of thousands at his Facebook page who assured him they’d  buy the book, and managers at many tourist venues around Pikes Peak also agreed to stock it. After the book’s release in October 2011, Daggett sold so many copies on Amazon that the book shot up into Amazon’s “hot new releases” list. It’s well-reviewed there, with 64 out of 67 reviews giving it the maximum five-star rating.

buy the book, and managers at many tourist venues around Pikes Peak also agreed to stock it. After the book’s release in October 2011, Daggett sold so many copies on Amazon that the book shot up into Amazon’s “hot new releases” list. It’s well-reviewed there, with 64 out of 67 reviews giving it the maximum five-star rating.

Daggett sold enough books that he quit his job in 2012.

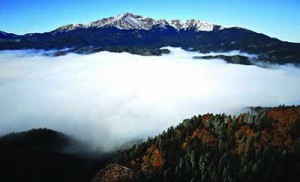

He’s had setbacks. The fires and floods around Colorado Springs in recent years have affected his earnings. But Daggett has 70,000 photos, many of which could have made it into the book. He’s come out with a soft-cover version of 365 Days and calendars. The books don’t just sell to tourists; locals also buy them, as do people, mostly military, who used to be locals.

“He gets a kick out of people who’ve moved away to Florida or Missouri, and who contact him to say what the photos mean to them,” says Williams. “Maybe they were depressed and they look at Shaun’s pictures and it reminds them about what’s beautiful, what they love.”

The book’s success meant that Daggett could do more charitable work. He helped the Wounded Warrior Project in 2012, and in 2013 he helped his friend Williams, a U.S. Army veteran of both Iraq and Afghanistan. Williams came home with a permanent disability, a back injury, and hopes for the kind of stem cell treatment Peyton Manning received. The Veterans Administration, however, doesn’t cover that procedure, which would cost $9,000. Daggett helped Williams videotape his own online appeal.

“I would have never have known how to go this route,” says Williams. “Every day we were brainstorming on how to get the money to make it happen.”

Williams now has the money for his treatment.

Daggett also gives time to others who hope to bring their own creative projects alive. “They tend to focus on how to make money,” Daggett says. “I tell them to stop worrying about that. Share your passion with the world; do it very publicly. If it’s good, people will pull your ropes. They’ll grab hold and pull you across. If it’s not good — well, failure isn’t the end of the world.”

A Colorado native, freelance writer Kristen Hannum no longer brings Southern relatives to the 14,115-foot summit of Pikes Peak. Too many of them faint.

See more of Shaun Daggett’s photos of Pikes Peak here.