– An Inside Look at Talbott Farms –

By Eugene Buchanan

You’ll have to excuse Charles Talbott if he’s allergic to peach fuzz. He’s been around it a long time.

Still, it’s an odd ailment for the sales manager of Talbott Cider Co., a division of Talbott Farms in Palisade. He’s a part of the sixth generation working his family’s Colorado peach farm outside Grand Junction. He grew up planting, picking and packing peaches for the biggest player in a region known for peaches. Talbott produces 25% of Colorado’s peaches, shipping the succulent morsels to 34 states. That’s a lot of fuzz.

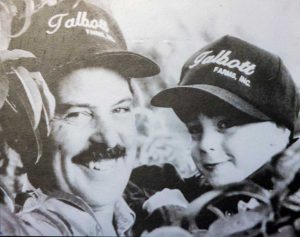

On the floor of his cidery’s taproom, a seventh generation Talbott works on his immunity, his hair barely more than fuzz itself. At just 7 months old — about the lifespan of your average peach, from bloom to cobbler — Wade Talbott reaches into a crate and chomps his gums into the soft, meaty flesh of a Freestone, its juice dribbling down his chin. He’s already showing an interest in the family business.

“He loves them — peaches were his first food,” says Mom, Hannah, Charles’ sister. “He’s already working in quality assurance.” Wade flashes a big grin behind the dribbling juice.

Indeed, it’s a true family affair at the orchard. There are nine different Talbotts working there, even after the passing of longtime peach patriarch Harry Charles Talbott last March at age 87 — his service drew a Who’s Who of residents in the region.

Charles’ father Bruce, president of the Colorado Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association, oversees the farm’s orchards and vineyards; Uncle Charlie serves as CFO and CEO; and Uncle Nathan handles production. The fourth sibling, David, branched off like a tree limb and is a local doctor, but runs his own vineyard. Charles’ brother Joseph is director of operations and Hannah is a supervisor.

The family’s roots in farming are deeper than those of its peach trees. Charles’ great-great-grandfather Joseph Evan Yeager moved to the Grand Valley from Iowa in 1907, starting a legacy that now includes 350 acres of peaches, 160 acres of wine grapes and 40 of miscellaneous fruits, including pears, cherries, apples and “test varieties” such as the peacotum, a blend of peach, apricot and plum. Talbott Farms also picks, packs and sells peaches for another 32 growers in the area, who dovetail their services.

One of these is Greg Morgan, who farms 5 acres nearby and is sitting next to me sampling Charles’ latest cider concoction. “I’m a small grower,” says the 30-year peach farmer. “I can’t afford the crew it takes to do things like spray, irrigate and pick. So, it’s a great relationship working with Talbott.”

“We operate their fruit,” chimes in Charles. “Some people want us to handle everything, while others want to do everything except the actual selling.”

While Talbott also supplies grapes for a quarter of the state’s wine, it is with peaches where its true colors — and flavors — shine.

“Talbott Farms is pretty darn good at what they do,” says Jeff Pieper, a pomologist, or fruit specialist, with the CSU Extension Office’s western region. “They’re the state’s biggest grower and are a model for production and product diversification. They’re pretty much the face of the industry.”

And despite their quantity, they value quality even more. “We’re the highest-priced peach in the nation,” Nathan says proudly. “It’s quality. I’ve heard people who’ve eaten Georgia peaches their whole life come and say, ‘I’ve been getting screwed down in Georgia. These are way better.’”

Indeed, the eastern side of the Grand Valley is the only region in Colorado able to sustain profitable peach production due to reliable irrigation water and warm temperatures, Pieper says. The western edge of DeBeque Canyon and Palisade and Orchard mesas are even better.

“Topographical changes there create a microclimate that protects the trees during spring or fall frosts,” Pieper says, adding that area peaches can also ripen on the tree longer than fruit shipped from farther away.

All this creates peaches that consumers with more discerning tastes than 7-month-old Wade cherish. “This area produces incredible-tasting fruit, to no credit to us,” Nathan says. “People who have never tasted one don’t know what they’re missing.”

FERMENTING A BUSINESS IN CIDER

Charles grew up working the farm doing a bit of everything, alongside immigrants from as far away as Thailand, Russia and the Czech Republic. He joined the Army instead of going to college, which is where he serendipitously learned how to brew and vinify. In trouble at one point and forced to live with an officer, the higher-up took him under his wing and taught him the ropes.

When Charles came back to the farm in 2015, he convinced his dad that they should add a cidery to their operations, using their leftover fruit. The idea blossomed, with its tasting room and cider division booming. Its bestselling libations, says Charles, include its Summer Sunset and Peach Habanero ciders (his favorite), followed by peach brandy and a peach wine spritzer.

“Only 1% of family farms survive the third generation, but we’ve made it to the sixth,” he says. “But we have to keep adapting. This is one way to expand and diversify.”

Charles is also part of a movement trying to build Palisade as a tourist attraction. He helped organize the town’s 10-year-old Palisade Bluegrass Festival, building a stage from apple crates at their taproom to host bands, comedy acts and more.

“We’re trying to put Palisade on the map as a farming mountain town instead of a ski resort town,” he says.

A QUICK TOUR

After sampling various ciders, we head into the factory. Our first stop: the company’s new Aweta Hyper Spectral AI machine, which uses a sonagram “flasher” to pre-sort the peaches. “It takes 96 pictures of each fruit per second through its optic-sorter,” Bruce says, “assessing everything from size, ripeness and seed splits to blemishes and bruises.”

Ones that make the cut get fed onto one conveyor for boxing and refrigerated storage, while processor-grade fruit goes elsewhere for cider, yogurt, wine, breweries and more. “It’s a pretty state-of-the-art scanner,” Nathan says, adding that they’re constantly working with Aweta engineers to tweak it.

The peaches end up in one of three main areas. Number ones are perfect and tray-packed into 16-pound or 20-pound boxes. Number twos are slightly off-grade, with a slight cosmetic issue, for buyers who want a discount (often canned or used for things like fundraisers). Number threes are process grade, perhaps with cuts, bruises or other blemishes, used for processing into brandy, puree, cider, juice, yogurt and more. Ones that are just plain ugly or too small (the machine’s sizer has 16 different settings), are discarded.

But it’s the number ones they strive for, because that’s what Palisade has become known for. “The first time I had a real Palisade peach, I was like, “Oh. My. God!” says Juliann Adams, who runs the nearby Vines 79 winery and helps promote the region. She eats them plain, grilled, sliced over ice cream, in salsa, as cobbler, in salad and more. “I even eat them in a sandwich like the BLP — Bacon, Lettuce and Peach,” she says.

Adams grew up eating Georgia peaches and says, “They don’t hold a torch to peaches from Palisade.” Even England’s Queen Elizabeth II, she adds, gets Palisade peaches delivered to her each year.

The reason lies in the area’s growing conditions. Palisade’s 4,700-foot elevation has a high UV index, Charles says, and the area has long, warm days and cool, arid nights, “perfect for building sugars during the day and acid at night.” Combined with sunshine, nutrient-rich alluvial soils and water from the Colorado River, the result is what many call the best peaches on the planet. “The nutrients are drawn up by the trees’ roots and travel through every branch to the ripening fruit,” Charles says. “And they’re picked ‘tree ripe’ to ensure maximum flavor.”

Which is where it can get tricky — a problem solved by “varietals.” A peach isn’t just a peach. From clingstones to freestones (in clingstones, the meat sticks to the pit; in freestones, it falls off), different varieties ripen at different times. In the olden days, everyone grew Elbertas, which they’d horse-and-buggy down to the fruit co-op by the river to load onto train carts. The whole picking-to-shipping season would be over in three weeks. So, the Talbotts began experimenting with different varietals to spread out the workload, hiring workers for the entire season instead of one big push.

About 10 varieties now make up 90% of the valley’s volume, Nathan says, all ripening at different times, sometimes just a week apart. And it all depends on the day the pit hardens. Come June, workers will cut into peaches on the tree daily; as soon as the pit is hard instead of soft, the countdown begins.

“It’s game-on from that day forward,” Charles says. “The pits all harden at the same time, but from then on different varieties ripen at different times. It’s 45 days from hardening for red havens and 65 days for O’Henrys.”

The first to ripen are usually semi-clingstones such as red havens around mid-July, followed by red globes and suncrests — the king peach of Colorado, providing about 30% of the state’s total. Crest havens, angelus and August ladies follow, before the biggest peaches, O’Henrys and Victorias, close out the season. “I like the late-season peaches better,” Charles says.

Talbott’s peach season now lasts from early July through the end of September, with only 24 hours from picking to truck. “We can pick them today and they’ll be on a shelf in Denver tomorrow afternoon,” Nathan says, adding the key is keeping their pulp temperature at 34 degrees at their refrigerated warehouse and during transport. “It’s a game of managing curveballs,” adds Nathan. “It’s 12 weeks of total chaos. I lost all of my hair in my early 20s.”

The first step in getting them to market, of course, is the picking. To do this, after pruning and thinning — which used to be done by stilt-walkers, who once appeared in New York’s Macy’s Parade — pickers use ladders to fill 30-pound kangaroo pouchlike picking sacks. Then they’re sprayed with water and covered with a tarp to cool, after being emptied into half-ton fruit bins tractored four at a time to the warehouse for sorting by the Hyper Spectral machine. Then they’re weighed, with grower and field information recorded, before heading into cold storage for daily distribution. The farm turns out 150 tons on a big packing day, helping Colorado rank seventh on the country’s peach producer list, providing 4.3% of the nation’s $521 million, 617,000-ton annual total (behind California, New Jersey, Washington, Pennsylvania, Georgia and South Carolina).

EYE ON THE WEATHER

Still, Mother Nature calls the final shots. The main disadvantages of growing peaches in Colorado are a relatively short growing season and the dreaded frost — especially in spring. “Our bankers breathe a sigh of relief every May,” Nathan says.

To that end, they keep a keen eye on the temperature. Get a freeze before the trees go dormant in fall, or after they’ve bloomed in spring, and the whole crop can be ruined, as it was in April 2020 when a late freeze destroyed 85% of the crop, the worst crop loss since 1999. And warm temperatures in February can awaken the buds too early, allowing them to succumb to potential frost later.

In the old days, smokey, diesel-powered smudge pots kept the orchards warm when there was a freeze. Nowadays, propane-powered wind machines combat inversions by blowing hot air back down so cold air doesn’t settle on the trees. Each machine can cover up to 15 acres.

Palisade’s location does the same thing, on a larger scale. When nearby Cedaredge hit 0 degrees in October 2020, Palisade only hit 10. “The eastern breeze through DeBeque Canyon brings warm air down,” Nathan says. “The cliffs heat up during the day, and at night, the breeze blows it right onto the orchards. It’s 10 degrees warmer than Grand Junction on any given night.” And that’s enough to save the crop.

That makes the Talbotts’ seventh-generation quality assurance worker, the juice-dribbling, 7-month-old Wade, happy.

Former reporter Eugene Buchanan explores the outdoors of Colorado and beyond from his home base in Steamboat Springs.