By Indiana Reed –

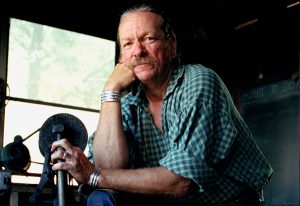

Photography by Jess C. Leonard –

It began with his fascination for old, worn structures.

In the 1970s, Joe DeLaRonde was finishing his undergraduate degree in zoology and psychology, with a minor in chemistry, at South Dakota State University when fate stepped in and changed his life.

“I was dating a girl (from Iroquois, South Dakota) and we drove by this building, and I have this terrible affinity for old abandoned buildings,” Joe says of the building that sparked his interest. He didn’t know at the time that it was a blacksmith shop. “‘Oh, that belongs to the old German blacksmith here. He’s just an old grouch,’ my girlfriend said.”

Driving by it regularly on weekends, he decided to stop one day. No one was there. Increasingly intrigued, however, he continued stopping by until the door was open. He walked into the world of the blacksmith shop run by a 10th generation smith, Wilhelm “Billy” Vogelman, originally from Emmetsweiler, Germany.

Billy was already in his 70s and the primary smith retained to forge and repair farming tools in the region. (He spent his weekends out on the farms, scoping out how to hone the plow equipment, which is why he was rarely at the shop when Joe was visiting his girlfriend.)

Joe’s parents weren’t initially enthusiastic when their son announced his “find,” as he had already been accepted to a master’s program to pursue a future career in animal behavior. But something about the dark, dusty, historic blacksmith shop called to him. He returned periodically to Billy’s shop, eager to learn more, and subsequently Joe entered into a three-year apprenticeship with the old German. Eventually Billy said, “I’ll sell this to you for what I paid for it in 1928: $3,500.”

“I got the shop and the teacher for $3,500,” says Joe, noting that Bill’s tutelage included decades of experience with his family’s secrets dating back to serving Kaiser Wilhelm II and his staff during World War I.

Joe was not completely devoid of artistic experience, as he’d also earned a scholarship to the Art Institute of Chicago, but the artisan craft of blacksmithing was completely new to him.

“I found it fascinating,” he says, and in addition to learning the craft, the inquisitive scholar within him propelled him into research. According to Joe, next to glassblowing, woodworking and pottery, blacksmithing is one of the oldest trades in the world. As he notes in his book, Blacksmithing: Basics for the Homestead, “Blacksmithing, as near as can be determined, originated in the Caucasus Mountains about 4,000 years ago … Blacksmithing is based on common sense and dealing with basic physical properties of the materials used: steel, heat and water. Mastering these takes enough skill and practice without cluttering it up with nonsensical gibberish.”

And indeed, he did practice and develop his skills. Billy started him out repairing farm equipment and sharpening the various plow lays, which had earned Billy his reputation with the farmers in the area. Joe also began visiting craft shows in the region and found an interest from attendees for what he calls “the artsy-fartsy stuff.” He then furthered his craft producing candlestick holders, door knockers, hooks, latches and other decorative items.

He may now downplay those early efforts, but today, in Colorado, in the rustic cabin in Mancos that he shares with his wife, Marlis, and their energetic chocolate Lab puppy Coco, evidence of his creativity in blacksmithing as an art remains. All through his craft show years, he enhanced his magic behind heating, pounding and shaping metal into utilitarian, as well as decorative, items.

Blacksmiths are widely assumed to be only farriers, pounding out horseshoes. But, early in his apprenticeship Joe asked Billy about horseshoeing — why wasn’t he crafting horseshoes?

“He looked at me over his glasses and said, ‘You’ll find a bigger fool than me to show you that s#*t.’ And I thought, good, I don’t have to worry about that,” Joe says. “I dodged a bullet on that.”

No horseshoes for Joe.

Fur Trade Rendezvous Circuit

During his initial years with Billy and first years in business, a young Joe secured a few retailers who purchased his decorative items wholesale, but then he discovered the Fur Trade Rendezvous circuit. Rendezvous events have blossomed and continued to grow in popularity in the areas of the world where fur trading was central back in the early 1800s.

The events are reenactments of the gatherings where trappers convened after a rigorous winter of trapping. Purportedly, as was part of the rendezvous 200 years ago, goods are traded, stories are told and fun is enjoyed by those attending. Today a rendezvous includes demonstrations of period skills including black powder shooting, archery and tomahawk throwing. Goods offered by the traders include period clothing, furnishings, camp gear, trade silver, animal skins, jewelry and a fascinating variety of other utilitarian and decorative items.

Axes made using three methods of construction: (left to right) felling, wrapped-eye and punched-eye.

“I went to my first rendezvous in 1980,” Joe says. “Then I began making tomahawks, axes and camp sets and knives, which I enjoyed much more than making fancy stuff.”

But one certainly shouldn’t say that Joe’s pieces aren’t fancy, depending on the definition of “fancy.” True, this is not ornamental work. The pieces are heavy and appropriately weighted, and the metal is forged and the handle designed to re-create an authentic period piece, capturing the essence of the historic fur trader tool. Given his authenticity and craftsmanship, he’s had museums and collectors contact him for authentication of pieces of his that they’ve stumbled upon — believing them to be antiques.

“They’ve seen my touchmark,” he says of the engraving that is unique to each craftsman. “The reenactors are from all over the world. I’ve shipped [tomahawks] all over Europe because apparently there are a lot people who do rendezvous in Germany. There are many people who come from (the former) Czechoslovakia and France to the U.S. rendezvous. I’ve also shipped some to Japan, but I think those are collectors. I don’t think they’re doing the fur trade reenactments.”

His basic style for the Colonial tomahawks has remained the same, as he stays true to history, although he has created variations based on requests and needs of customers, including adapting styles recognized from the French and Indian wars. His more complicated pieces could involve 10 to 15 hours of work, which sets Joe’s pieces apart at the various rendezvous events, and prompted interest (and ultimately orders) through his website.

A military focus

“About six or seven years ago I had a Navy SEAL contact me, and he said, ‘I need a belt ax, and I need it to do this and this and this,” says Joe, who agreed to craft a prototype, which would be a utilitarian piece that not only had the front blade for traditional use, but also additional features that were of need to the military units on the ground in Iraq. “I made it up for him, sent it to him asking for any changes, and about a month later, I got an email that said, ‘Perfect, just what I wanted. Send me six more for the rest of the team.’ That got me started with making items for the military.”

Since that time he’s made thousands of custom pieces for various branches of the military, as well as first responders in the states. When he has multiple orders including rendezvous folks or collectors, he always moves the military or first responders to the head of the list. Joe is a veteran, having served in combat infantry in Vietnam in 1966-1967, at a time before he ever knew about blacksmithing and how his creations could assist enlisted members and first responders in the field.

The shop

Joe’s unique pieces are created one by one in his shop down the hill behind the cabin, in a structure that originally was a lean-to for horses that once lived on the property. It’s dark and cold, and filled with dozens of unique tools that would make an antique dealer salivate. The rugged anvil, which is the centerpiece of the small shop, has seen so many years of “pounding” that it is slightly bowed from the thousands of pieces Joe, and Billy before him, have crafted. He has no idea how many pieces he’s crafted in nearly 50 years, but the anvil has been there for all of them.

“I numbered the first thousand tomahawks, and they were gone within a year,” he says. “And that’s I couldn’t tell you how many thousands ago. I made a large and a small of each style.”

If the anvil is the heart of the shop, the forge is the essential piece of equipment for a blacksmith. For the layperson, it could be described as a giant open oven (envision a big indoor barbecue without a grill) with a large overhead vent. It’s coal-fired, with the coal stoked by a fan to inspire the forge to burn hot.

“Basically all you need is something that will blow air up through the coal,” he says, noting he’s now able to source his coal locally from the mines near Hesperus. “In the old days, before electricity, forges were run by big bellows. Some guys go through all kinds of elaborate stuff to light their fire, which I’ve never quite figured out. It doesn’t take much to get it heated up.”

And therein lies one reason the shop is cold and dark. The forge, once fired up, produces a generous amount of heat, plus part of the art for a blacksmith is his ability to gauge the metal. These craftsmen know just how long to heat the metal by its color in order to begin the process of creating a unique piece. Bright lights can impede that process.

“It does get warm (in the room). Problem is this time of year my feet freeze,” he jokes, noting the shop has no constructed floor — only dirt with a generous layer of coal soot.

The next generation

While he remains passionate about his craft, Joe recognizes that it may be a dying art. Currently he has a young apprentice who, several times a year, is able to escape her day job in Utah and join him for a long weekend to advance her skills. But at this time she’s the only one who has picked up the passion. He’d like to see more handcrafted products at the rendezvous, and is somewhat dismayed that many of the items brought to the events are coming from India and Pakistan.

“Do blacksmithing! It’s lots of fun,” notes Joe, saying that Billy, the old blacksmith, was 72 when he took him on as an apprentice. “I’m 75 and I’m still doing it. Age is a relative thing. I got hooked on it and the rest is history.”

Indiana Reed is an award-winning journalist and communications consultant based in Durango. Working from her cozy country home in rural La Plata County, she has earned a national reputation for her quality writing about businesses and the arts.

Interested in learning the art of blacksmithing? Joe DeLaRonde hosts occasional seminars for aspiring blacksmiths, generally in the late spring or early fall. Learn more about DeLaRonde’s work at www.delarondeforge.com.