By Amy Higgins –

Photos Courtesy of The History Colorado Center –

It seems like an electric vehicle hit the scene only a short time ago. In reality, this modern marvel made its way to the future from a distant past. In Colorado, it was Oliver Parker Fritchle whose showpiece graced the electric vehicle scene in the early 1900s. Prior to that, the first EVs started showing up around 1890.

The First EVs: Driving the hype

Fritchle was born on September 15, 1874, in Mount Hope, Ohio. In 1899 he moved to Colorado to work as a chemist and assayer at Excelsior Mines in Frisco, where he helped install the electrical works in a hydroelectric power plant. Soon he was in charge of the bulk of the electrical duties. But by 1900 he moved on to work as a commercial chemist in Denver.

Yet, he didn’t leave his interest in electricity behind. Fritchle was enamored with cars, particularly the electrically-powered vehicles. He began repairing the first EVs in the Denver area, all the while developing his own rechargeable battery.

In 1906, Fritchle’s first EVs came on to the market and, in 1908, The Fritchle Automobile and Battery Company was established.

Fritchle electric cars were distinctive because of their ability to travel 100 miles on one overnight charge. “No other electric cars had batteries like the Fritchles,” reported Clark Secrest, editor of Colorado Heritage magazine in a 1999 article.

Fritchle was so confident that his EVs lived up to the hype he touted that he challenged other car manufacturers to a cross-country excursion. “No one took him up on it,” said Leigh Jeremias, curator of manuscripts and special collections at the History Colorado Center. So, on October 31, 1908, Fritchle set out alone in a Fritchle Victoria on a 28-day tour (20 days of drive time) from Lincoln, Nebraska, to New York City.

Fritchle packed tire repair tools, one extra inner tube, a spare tire, an iron jack, a tool kit, a set of tire chains, a hand lamp “for reading sign boards,” a canvas water bucket, extra fuses, sulfuric acid and ammonia to service the batteries, a thermos, two lap robes, maps, a camera, a tripod and two suitcases with personal supplies.

He was so secure in his vehicle’s power that he did not pack a spare motor or any other parts, except for the tire and tube. In all, the car weighed around 2,100 pounds, 800 of which were from the battery alone.

After his first day on the road, Fritchle wrote in his journal: “It was a damp, cold morning, just about freezing and very hazy. I encountered some very bad roads, and it being my first day out, I was discouraged and doubted very much whether I would ever finish the long tour which I had planned.”

Fritchle drove day and night through the country, jerking over rigid rocks, slogging through dense mud and oftentimes carving his own path because none were available. Without a windshield on his car, he had little protection from the elements.

About every 100 miles, Fritchle charged his vehicle, mostly at municipal electric plants and privately owned companies like his factory in Denver.

Heads turned when the Fritchle car came to town. “In most of the towns which I passed through, an electric auto was a great curiosity, and very interesting, especially to the men connected with the electric plants, who were always very obliging to me,” Fritchle wrote.

Horses were terrified of his peculiar machine. In one instance in Weston, Iowa, he came up on a carriage drawn by a four-horse team. Two of the horses were so spooked that they, “…wheeled suddenly, broke the tongue and ran away. I do not know whether it was on account of it being an electric and running so quietly, or on account of the uncommon Victoria top,” he surmised.

Fritchle logged everything about his journey, careful not to leave anything out. “He was a very particular man,” Jeremias said. “He documented everything. Everything.” Not only did he keep track of his whereabouts and findings, he also recorded such items as his daily food intake, the amount of exercise he accomplished and how well he slept.

In all, Fritchle traveled 2,140 miles. When the tour ended, Fritchle assembled the promotional book 100-Mile Fritchle Electric. In it he summarized: “The tour was undertaken to test for my own satisfaction the durability of one of my electric automobiles away from the factory on country roads, at a season of the year when the roads could not be in their best condition, and in cold weather when the battery is sluggish and does not give as high capacity as in the warmer period. Knowing that my machines are well constructed, that this was a regular stock car (not built for the occasion), it is still astonishing to me how well it withstood the rough usage.”

“Twenty days is pretty impressive considering the elements and stopping to take photographs along the way,” Jeremias said. Fritchle continued his journey in his electric car to Washington, D.C., and then returned home, without any mishaps.

Ranging from $2,000 to $3,600, Fritchle’s first EVs were expensive compared to the $440 to $550 it would cost for a Ford gasoline car. However, they roused the “elite and wealthy” population, particularly prominent women, because they were cleaner than gasoline cars and the inside was large enough to accommodate large hats, which were popular accessories in that era.

Denver’s “Unsinkable” Molly Brown was also impressed with the stunner, so she purchased a 1910 model and drove it for several years. Denver Gas and Electric Company and Daniels & Fisher department store each owned Fritchle electric trucks.

After completing the promotional tour, Fritchle continued the journey in his electric car to Washington, D.C.

“His is a nature that could never be content with second place and he has therefore always striven for perfection, never stopping short of the successful accomplishment of his purpose,” said Wilbur Fisk Stone of Fritchle in a 1918 transcript titled History of Colorado.

Holding the charge

Unfortunately, the first EVs fell victim to the affordable and popular self-starter gasoline cars and, despite his ambition, in 1917 The Fritchle Automobile and Battery Company closed. The national recognition Fritchle garnered fizzled.

“The story sort of stops for him, I think in a lot of people’s minds, with the failure of the electric car, but he kept going. He was an inventor. He wasn’t just an electric car guy, he was an inventor,” Jeremias said.

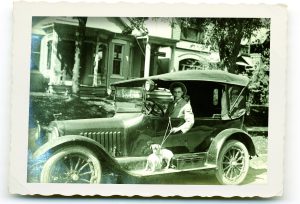

Fritchle and his team of car builders pose for a picture in front of The Fritchle Automobile and Battery Company in Denver.

Nearly 100 years later, an original Fritchle electric automobile, number 283 (out of approximately 500), is sparking curiosity at the History Colorado Center. But getting the vehicle to the center wasn’t a simple endeavor.

In 2012, number 283 was gifted to the History Colorado Center. The vehicle was stored in an off-site location where it would stay until its move to the museum.

But disaster struck.

The location suffered a water main break underneath the building. Water accumulated, damaging the foundation. An exterior wall collapsed, causing the roof to fall on top of the vehicle, compromising the frame. “It was a complete mess,” Jeremias said.

The conservator repaired the frame of the car and brought it back up to its original form. The doors and windows were realigned back to their original location as well. “Shockingly, for what happened, it could have been so much worse,” Jeremias said. “I think that says something about the frame of the vehicle and how well made it was.”

While the conservator restored number 283 back at the museum, a large cutout of the Fritchle automobile was on display along with its charger and a short narrative.

With a lengthy restoration process and insurance dealings, it wasn’t until August 2014 that one of the first EVs settled into its new home at the “Denver A to Z” exhibit at the History Colorado Center in Denver.

“It has always been my ambition to do something extraordinary. While my efforts have been relentless, my accomplishments have not fully gratified my ambitions. However, I am proud of my efforts and feel that no one has any reason to say I did not try to do something worthwhile,” Fritchle wrote in his autobiography.

Today, the Fritchle vehicle serves as a reminder of how history tends to repeat itself. Brilliant minds are continually blazing new trails, but sometimes it just takes some time — or maybe a century — for innovation to really catch on.

Amy Higgins is a freelance writer from Centennial. She’s fascinated by the things that power our lives, especially if they’re from Colorado. Have a local story idea? Email her at ahiggins@coloradocountrylife.org.