By Amron Gravett –

Photos from the Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College –

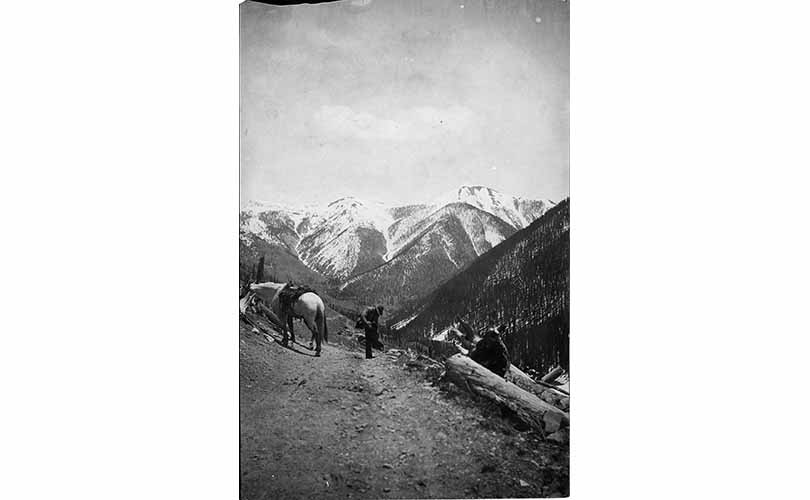

Tough men, Ouray, CO, c. 1910. Photographer Chase & Lute.Electricity came to southwestern Colorado back at the turn of the 20th century, not to power homes, ranches and small towns, but to run mining operations and bring the gold and other ores out of the mountains. That meant generating and distributing electricity in some of the most remote and geographically challenging terrain in the country. That also meant that the men of early electrification in the San Juan Triangle were some of the toughest men in the region’s history.

“These were rugged men who worked despite the handicaps of weather and rough terrain of the Colorado mountains,” writes Durango author Esther Greenfield. “Blizzards, swift and sudden snow slides, deadly lightning, and mudslides were everyday occurrences for them.”1 The crews suffered many injuries and accidents such as strained backs, objects in their eyes, electrocutions, drownings, even suffocation from avalanches. This work was not for the faint-hearted.

Greenfield, who connected with the tough men and hard work of this bygone era through an image collection at Fort Lewis College, believed the story of these men was worth telling. And last October, her book Tough Men in Hard Places: A Photographic Collection was released.

Beginnings of Book

Back in November 2012, Greenfield first penned an article for the Durango Herald reviewing the amazing image collection of Philip Chester “P. C.” Schools, longtime superintendent of the Western Colorado Power Company. Her article, “A Powerful Look at Power” was the result of her archival work at the Center of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College.

Back in November 2012, Greenfield first penned an article for the Durango Herald reviewing the amazing image collection of Philip Chester “P. C.” Schools, longtime superintendent of the Western Colorado Power Company. Her article, “A Powerful Look at Power” was the result of her archival work at the Center of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College.

Since 2007, she has worked as a volunteer alongside archivists, curators, librarians and other volunteers, processing, documenting and organizing a collection of over 8,000 photographs from Schools and the Western Colorado Power Company. These photos provide access to the electrical innovations of the time and the story surrounding their introduction.

P.C. Schools never left the house without his camera, according to his daughter, Phyllis Schools Case. “He always had it because he felt the need for taking pictures of lines as they were constructed. He always marked where they were and the dates. So he had an exceedingly good record of the power company activities. The pictures of the plants are excellent.”2

Creosoting stubs, Rockwood, CO, c. 1909. Photographer P.C. SchoolsIn 1999, Todd Ellison interviewed Case for the oral history collection at the Center of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College. In that interview, she recalled how her dad would build lines out with the crews in the summer and come home on the weekends. She and her sister would sometimes visit the sites with their dad. “We walked the flumes when they were just in construction where there were just two by twelves across the top. We’d walk across that with swift running water. My mother would stand off to the side tearing her hair out.”2

Tough Men in Hard Places is also the story of the experiences of the linemen, engineers, bull gangs, ranchers, farmers and housewives of that era. For the last 120 years, multi-generational families of the region have spent their careers recording, repairing, and running the power plants that brought electricity to the area.

“Families of electrical plant workers throughout the region knew one another and formed a small but cohesive social network. In addition workers in the plant had to coordinate carefully with one another and work as a team in order to literally keep the lights on for their neighbors, something they shared as a great responsibility,” says Bruce Spinning.3

The Schools’ are an example of this type of family. P. C. Schools was sent to work in the mines of Idaho at age 9. In his youth, electricity was rarely talked about but Schools had an inkling that it was ‘the coming thing’ so he chose to make it his career. He went to Washington State College to get a degree in electrical engineering in 1905 and then came to Colorado to work in Telluride’s Tomboy Mine in 1909. Fifteen years later, he sent for his father, Nicholas Schools, to come out and work for the Western Colorado Power Company as well. Eventually P. C. Schools went on to become the chief engineer and later superintendent of WCPC, dedicating 45 years to the company.

Saved by AC

Joe Lounge, exhibit director of the Powerhouse Science Center in Durango, explains that the early mining operations switched from wood and coal power to alternating current or AC power to solve the problem of remoteness. “They needed some way to get energy over quite a distance from where it was being generated to where it was needed in the mine. AC can go long distances. DC cannot go long distances. So AC is going to be more successful.”4

Th e Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition introduced AC power to the masses in 1893. Although the power was outlawed in some states of the Eastern United States because it was deemed too dangerous, remote southwestern Colorado was already using it in generating stations by that time. Bringing AC power to the mining operations of southwestern Colorado is credited to Lucien L. Nunn. “Nunn was beyond a doubt the real pioneer of long distance transmission of power,” says J. A. Bullock, former supervisor at WCPC.1

e Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition introduced AC power to the masses in 1893. Although the power was outlawed in some states of the Eastern United States because it was deemed too dangerous, remote southwestern Colorado was already using it in generating stations by that time. Bringing AC power to the mining operations of southwestern Colorado is credited to Lucien L. Nunn. “Nunn was beyond a doubt the real pioneer of long distance transmission of power,” says J. A. Bullock, former supervisor at WCPC.1

The Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant was located near Ophir in San Miguel County at 8,720 feet. Since 1887 it had powered the Gold King Mine located 2.6 miles away and over 2,000 feet above. Olaf Nelson, then owner of Ames, was going bankrupt and needed a way to save his investment. He agreed to let Nunn experiment with the use of AC power beginning in 1891. Nunn rigged up his operations, including a Westinghouse generator, and the AC current ran to the Gold King Mine uninterrupted for 30 minutes. It was the first commercial high-voltage alternating current power system that both generated and transmitted electricity for commercial use. (Although several upgrades have been made at the Ames power plant, one can still witness the massive 3,600-kilowatt AC generator turning loudly, but slowly, at 225 rpm.)

AC power provided a powerful solution to the mines of the region that were in rapid decline due to pending bankruptcies. They had grown dependent on wood and coal sources to power their machinery. The former was rapidly disappearing and the latter was proving too expensive and inconsistent as a resource because “when snow blockaded the railroad, coal supplies would run low, forcing the mines to close.”5 Regional power companies invested in the infrastructure needed to migrate to AC power and the revival of the mining industry took place.

Western Colorado Power Company

During the boom of new power companies, Greenfield writes “there were about 30 separate power companies operating in Colorado to bring electricity, power, and conveniences to rural homesteads. One by one, however, they went out of business or merged.”1 But saturation and consolidation were on the horizon. The Western Colorado Power Company was organized in 1913 and by 1914 had consolidated eight major power companies of the region: Delta Electric Light Company; Durango Gas and Electric Company; Montrose Electric, Light and Power Company; Nunn’s Telluride Power Company; Ouray Power and Light Company; Ridgway Electric Company; San Juan Water and Power Company; Telluride Electric Light Company.6

Some of the earliest generating plants operated by these companies are still in use today. Some have been adapted and given a new life outside of power generation. The Powerhouse Science Center, formerly Durango Discovery Museum, is one of the American West’s first AC power plants. Built in 1892 by the Durango Gas and Electric Company for coal-fired AC power, it later became part of the WCPC grid. Today, the building and some of the original machinery has been preserved and made available for educational use, where exhibits and events share the story of the building’s history as well as the history of electrification.

The story of the Silverton Substation and the Tacoma Plant is equally fascinating. In 1906, the Silverton Substation was built distribute power from the Tacoma plant located 25 miles south. “The new power plant at Tacoma was a hydro-electric facility generating 6,000 horse power and feeding a 44,000 volt line up the Animas Canyon to the Silverton Substation building. Here, four large transformers dropped the voltage to 17,500 volts and sent it on to the mines.”5

Power for Rural Areas

The mines and the town, now served by WCPC, had electricity. But, in the 1930s, only about 10 percent of rural farms and ranches had electricity. That would change with the creation of the Rural Electrification Administration in 1935. This allowed friends and neighbors to come together and borrow money from the REA to form their own electric utility.

By 1938, San Miguel Power had opened in Nucla and Delta-Montrose Electric got its start near Delta. While WCPC had refused to build the lines to serve the farms and ranches, the company did eventually agree to supply the needed power once the co-ops had built the lines. By 1939, the REA movement had spread to the Cortez area where Empire Electric began building lines to serve its first 50 members and to the Durango-Ignatio where today’s La Plata Electric got its start.

The demand for power, both through the electric co-ops and through WCPC, continued to grow. This brought economic viability to the area, kept the mines open and operating, provided power to homes and ranches and added jobs throughout southwestern Colorado. Those tough men who chiseled and drilled electric poles into hard rock and strung wire along steep mountainsides had brought reliable electricity to this corner of Colorado.

Greenfield’s book is an intriguing reminder of how hard these pioneers of history worked to get us to where we are today.

Amron Gravett was born and raised in Tacoma, Washington, the namesake of Durango’s Tacoma power plant. She is an indexer and librarian. Her book Chimney Rock National Monument was published in 2014. www.AmronGravett.com.

Photographers James Orndorf and Amadee Ricketts live near Durango. You can see James’s work at roughshelter.com, and Amadee’s at textless.tumblr.com.

References: 1. Greenfield, Esther. Tough Men in Hard Places: A Photographic Collection. Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Books, 2014 2. Oral interview with Phyllis Schools Case by Todd Ellison. https://swcenter.fortlewis.edu/finding_aids/mp3/FLCu004547.sideA.mp3 3. 2010 Durango Discovery Museum Historic Exhibits Master Plan. powsci.org/download_file/view/537/301/ 4. Oral interview with Joe Lounge, by Amadee Ricketts, December 2014. 5. San Juan County Historical Society, Annual Publication, Summer 2006. http://www.sanjuancountyhistoricalsociety.org/2006Courier.pdf 6. Collection M 002: Western Colorado Power Company Records, Introduction. https://swcenter.fortlewis.edu/finding_aids/inventory/wcpc.htm 7. History of LPEA: Yesterday and Today. http://lpea.com/company_info/history.html 8. Colorado Rural Electric Association: Our Mission. http://www.crea.coop/About/OurMission.aspx